It has been such an honor to work with Three Rooms Press on the publication of MY VIETNAM, YOUR VIETNAM, and I’m so excited to see what we will accomplish together during this year. Below is an excerpt from the interview with Kat Georges. You can read the full interview here.

Interview by Kat Georges

All other photos © The Archives of Christina Vo

I first met MY VIETNAM, YOUR VIETNAM author Christina Vo via Pitch-o-Rama, an event where agents and publishers get a chance to meet with dozens of authors in a very short amount of time to learn about their upcoming projects. And what a project Christina proposed: a dual memoir sharing the stories of her father, who escaped to America from Vietnam after the fall of Saigon, and Christina herself, who was raised in the US and opted to move to Vietnam for years in search of connection to her ancestoral past. The first read through the manuscript was so powerfully moving, I became a huge fan and ardent supporter. With the publication of MY VIETNAM, YOUR VIETNAM just a few months away, I sat down with Christina to find out more about the impetus behind creating this project and her unique perspective on how, 50 years after the fall of Saigon, the wounds of war are finally beginning to heal.

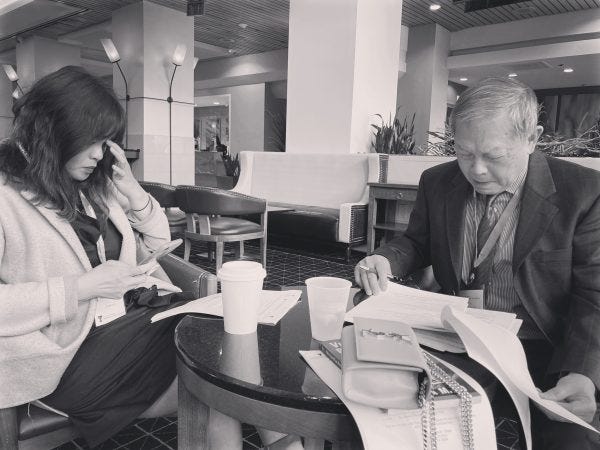

Christina Vo with her father, Nghia M. Vo

Kat Georges: MY VIETNAM, YOUR VIETNAM is a dual memoir, sharing two extremely differing viewpoints of the country of your ancestors. What prompted you to take this approach to this book?

Christina Vo: A series of events spanning decades led to the publication of this book. In 1997, a few years after my mother passed, my father wrote a memoir about Vietnam and rebuilding his life in the States. Since it was his first book, it was a mixture of personal storytelling and history. Since this was his first book, his writing voice didn’t quite feel consistent, as a result the book was difficult to read.

Then, five or six years later, when I was living in Vietnam, I was on a trip with friends in Hoi An, and I shared with them how I wanted to write another book about my father’s life. I had no idea how/when I would do it but I knew that I would.

Finally, the last time I ventured to live in Vietnam, I was in my late 20s and writing became part of my life for the first time. My early writing focused on Vietnam and my mother, mainly because I desired to keep memories of her and Vietnam alive in my heart and mind. After a few years, I nearly completed a manuscript about my family and Vietnam, and then shelved it for about a decade. My Vietnam story didn’t feel powerful or compelling enough as a singular story to get published.

During the pandemic, when I moved to Santa Fe and found myself with more time to think and process, it suddenly hit me that the way both of these stories about Vietnam — my father’s and mine — felt complete was by combining them and allowing the contrast to show depth and also to show parts of our relationship through this connection around Vietnam. There was a sort of completion by joining the two stories together in a way the singular stories did not possess.

KG: One description that is quite striking is the idea of “visible life” in Vietnam. Describe what this means, and how it differs from life in the US. Did the concept affect the way you approach life now?

CV: When I was leaving for Vietnam the first time, my then stepmother, who was also Vietnamese, mentioned “visible life” by saying something along the lines that life in Vietnam was so visible. That phrase certainly stuck with me while I was settling in and understanding life there.

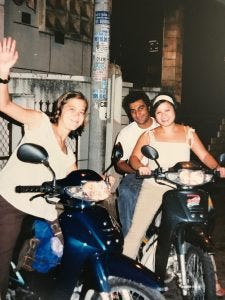

On the ubiquitous motor scooters in Vietnam

By visible life, you can literally see life being lived all around you. For example, if you wake up early and go to Hoan Kiem Lake in Hanoi (or any park), you’ll see hoards of people doing aerobics, jogging, playing badminton, and some who even bring their own dumbbells from home. You can see people sipping their cafe sua da (iced coffee) or eating pho. When you walk/drive around, you’ll see motorbikes everywhere and you’ll see them transporting the most random things, whether it’s a large tree, a tall mirror, or a basket full of live chickens. You can visit the fresh markets in the morning, or in Hanoi, there’s also a beautiful flower market you can literally drive through as early as 3am. The street level of homes sometimes pass as storefronts, and many of these storefronts are open so you can also see inside from the streets. You just see life. Everywhere. And there’s something about that “visible life” that for me made me feel much less alone.

Well, I couldn’t really replicate here what I had in Vietnam and what I gained by feeling so close to people and so much more entrenched in the community. I certainly miss the hustle and bustle of Vietnam and that ‘visible life’. To some extent when I moved to Santa Fe from San Francisco during the pandemic, there was something about the quaintness that reminded me of Hanoi, almost as if I am living in a place where time doesn’t move as quickly, and for whatever reason, that sense of time brings me back to Hanoi. Of course, Santa Fe doesn’t have the ‘visible life’ but it does have some level of simple charm that Hanoi had twenty years ago.

I do feel that the ‘visible life’ impacted the way I lived when I returned to the states. There’s a part of me that wants to open my home and life to people. In San Francisco, I regularly hosted parties, small gatherings, and salons — and I believe that was a way for me to bring more life to my home. Maybe this way I could compensate for not having that external visible life. But the “visible life” doesn’t really translate directly from Vietnam to the US. I don’t think the closeness of life, the visibility of life could be replicated here.

Please check out the full interview here.